Methodology

What is Translation?

A translation takes place when a message1 originated in a particular language (source language) is rendered into a different language (target language). As a process, translation generally involves three stages:

I. Analysis of the text to be translated

The translator needs to first understand the meaning of the text in the source language conveyed through individual words (morphology) as well as their order, function, and combination (syntax).

II. Transference of the text’s information

The translator takes the information gathered in his previous analysis and then, having the target language in view, seeks an appropriate equivalent rendering of the information.

III. Restructuring of the text translated

The translator is to formulate the information in the target language, according to the grammatical rules, conventions, and particularities of the target language in question.2

What is Theological Translation?

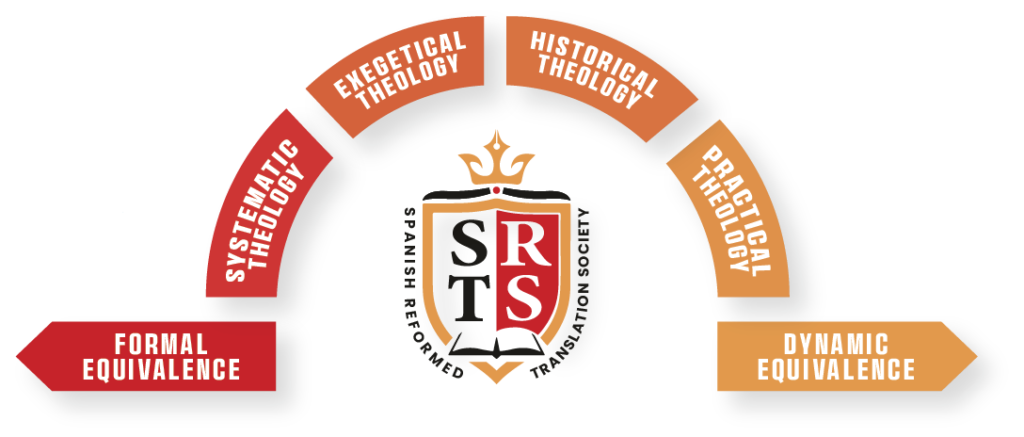

Theological translation involves all the stages explained above, applied to a text of a theological nature. It is important to mention that theological translation does not refer to the translation of the Bible, as important as it is. Rather, it refers to the translation of resources whose content is related to any of the branches of the theological encyclopedia, such as:

- Exegetical theology

- Systematic theology

- Historical theology

- Practical theology

- And other related fields

How Is Translation Done?

Usually, translation methodologies/theories swing back and forth between two postures:

1. Formal Equivalence (FE) – Source Text Priority

- This approach prioritizes the source text by rendering a literal word-for-word translation into the target language.

2. Dynamic Equivalence3 (DE) – Target Audience Priority

- This approach focuses on the target language’s culture, context, and audience.

- The rendering of the source text must be as natural and equivalent in meaning as possible in the target language.

How SRTS Suggests Translation Be Done

SRTS encourages all Spanish-speaking brothers and sisters involved in theological translation to remember that:

- Translation is not recreation.

- It requires neither originality nor authorship from the translator but rather faithfulness to an author’s work.

- The translator must have ingenuity but respect the limits of his jurisdiction.

- Rendering a message into a target language that was not actually expressed in the source language can be a transgression of the 9th commandment.

Ethical Responsibility in Translation

Translation is an ethical task, and SRTS encourages partners to perform this work in a Christ-like manner.

Key Aspects SRTS Recommends for Theological Translation:

I. Identify the Type of Theological Text to Be Translated

- Identify the type of theological text to be translated and employ the most suitable methodology for that material: within a diverse theological textual genre, there are materials with particular degrees of specificity or technicality and this needs to be held into account. For example, the lexical precision of a text on exegesis (depending on its level/purpose) or systematic theology requires from the translator a certain inclination toward the FE.

- Words bear a considerable semantic weight, especially in exegetical and systematic theology4; if inequivalent or inaccurate words are used to translate these types of contents, then probably a different thing will be said.

- Concerning historical and practical theology (depending also on their relationship to the previous two disciplines), these tend to lean more toward narrative or culture-oriented content. For these types of resources, the theological translator may feel inclined toward the DE.5

The following diagram helps to explain what was just said above.

II. Keep in view the purpose and audience of your text

- SRTS, for instance, prioritizes texts of a more academic and theological nature. These were written in academic contexts for academic purposes.

- Theological translators must uphold high academic and theological standards while remaining faithful to the original purpose and audience.

III. Use a Glossary for Theological Terms

- SRTS will make a theological glossary available for our partners in Spanish as a specific target language.

IV. Follow the Specific Grammatical Rules for Spanish

- The quality of translation should not be degraded by neglecting linguistic standards.

- This applies to text translation, subtitling, and dubbing.

V. Exercise Quality Control on the Final Product

- Review the final product thoroughly.

- SRTS encourages every theological translator to self-review their work, while editors and revisors also conduct reviews.

Who Should Translate?

Theological translation has been a powerful instrument for advancing the Kingdom of God throughout history.

- Confessional, Evangelical, and Reformed theological translations have historically upheld high standards of quality.

- SRTS encourages all partners to translate with excellence for Christ’s sake.

- Selecting a suitable translator is crucial.

- If no translators are available, partners should consider training their own theological translators.

- SRTS encourages partners to financially honor, as allowed, those to whom the Lord calls to such an important task.

Who is a Theological Translator?

SRTS suggests the following qualifications when selecting a theological translator:

I. A Theological Translator Must Be a Born-Again Christian

Jerome, Wycliffe, Luther, and Tyndale teach us that a prerequisite for a theological translator is the certainty of constant invocation and reliance upon divine grace for the fulfillment of his endeavors.6

II. A Theological Translator Must Have Mastery of Both Languages

- English (source language):

- The translator must have a high level of academic reading and writing.

- Spanish (target language):

- The translator must have mastery of all language skills, as Spanish must be his native tongue.

III. A Theological Translator Must Be Well Acquainted with Reformed Theology

- Because of the technical and academic nature of Reformed theological texts, which were mentioned above, the theological translator needs to be well informed in this area of Christian knowledge.

- It is not enough to have a grasp of the general use of the languages; the translator needs to be well acquainted with the Reformed theological jargon and tradition in both the source and target language.

IV. A Theological Translator Must Have Strong Writing Skills in Spanish

The theological translator must be able to compose writings in an orderly and coherent manner. This is important because he will constantly carry out literary expressions of theological content in the target language.7

V. A Theological Translator Must Have Skills in Reformed Theological Research

Sometimes, the challenges a theological translator faces cannot be directly solved since many of the authors quoted or studied have since long passed away. It creates for the translator the need to be fast, accurate, and precise in his research while solving different issues experienced when translating.

VI. Should a Theological Translator Utilize Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) Tools?

These tools enable the theological translator to perform his task faster and interact with materials in contemporary formats. To those interested in using Artificial Intelligence, it is advised to limit its use to formal (microstructural [orthographical/syntactical] and macrostructural [formatting] corrections) and not material (compositional/reformulative8) aspects of translation.

VII. The theological translator needs to know both the source context and the target context

Contexts influence language and vice-versa. Knowing the contexts behind the language usage will allow the translator both to perceive and communicate important cultural aspects attached to the meaning of a text.

- Within the target language, there also exists an ecclesiastical context. Knowing the latter allows the translator to contextualize the theological information. For example, a formal equivalence of the expression “Westminster divine9” into Spanish can create issues within the Hispanic Reformed church due to the influence of the Roman Catholic practice of beatification.10

Our Work

Translation Workflow

SRTS follows a rigorous multi-step process to ensure that every translation is faithful and precise. Our workflow upholds the highest academic and editorial standards to produce translations that serve readers with clarity and accuracy.

Translation Process

- Translation – Theological works are translated by qualified people with linguistical and theological knowledge.

- Revision – The team reviews and evaluates the accuracy of the translation, comparing it to the original text to maintain the integrity of the content.

- Editing – The text is refined for stylistic clarity, coherence, and accessibility in the target language, ensuring it remains faithful to the original while being engaging for Spanish readers.

- Proofreading – Every translation undergoes meticulous final checks for grammar, syntax, and typographical accuracy before formatting.

- Formatting – The work is professionally formatted to meet publication standards, ensuring optimal readability and presentation.

- Publication – Once finalized, the translated work is distributed in print and digital formats, making it accessible to seminaries, churches, and individuals.

Each step in this process is designed to honor the integrity of the original work while making it accessible for the Spanish-speaking Reformed community.

Works We Prioritize for Translation

Academic Reformed Theological Works

We prioritize high-quality academic resources that uphold the rigorous standards of Reformed theological education of doctrinal precision and biblical fidelity.

- Primary Sources – Foundational theological works from the Reformation and Post-Reformation eras.

- Secondary Sources – Scholarly commentaries, systematic theologies, and doctrinal studies that build upon Reformed theology.

Experiential Devotional Works

Recognizing that theological knowledge must lead to personal and spiritual transformation, we translate works that nurture biblical piety and deep communion with Christ.

- The Devotional Life of Seminary Students – Encouraging spiritual formation alongside academic study.

- The Personal and Spiritual Experience of Biblical Truth – Cultivating a Christ-centered experiential application of theology in all of life.

Suggest a Work for Translation

Would you like to help bring a key Reformed work into the Spanish-speaking world? SRTS prioritizes the translation of academically rigorous theological works and experiential devotional literature that will equip pastors, seminary students, and believers with faithful, Scripture-centered teaching. If there is a particular work you believe should be translated, we invite you to partner with us in this vital mission.

- Sponsor a translation – Support the funding of a specific theological work.

- Collaborate with us – Churches, seminaries, and organizations can partner in translation efforts.

- Recommend a work – If you have a suggestion, we would love to hear from you.

References

- Even though such a message can have a written, oral, visual, or audiovisual form, SRTS’s translation guidance will focus on the written form.

- Eugene A. Nida, The Theory and Practice of Translation, vol. 8, Helps for Translators (Leiden: E. J. Brill for the United Bible Societies, 1974), 33.

- Eugene A. Nida, Toward a Science of Translating: With Special Reference to Principles and Procedures Involved in Bible Translating (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1964), 165-71.

- Clearly, there are also resources from historical theology, and practical theology containing segments in which there might be a lot of theological precision or technicality.

- Again, resources from any of these categories can have segments with different theological features. However, it is now clear to the reader what SRTS suggests concerning these types of materials, whether they be whole books or segments of books.

- Frederick C. Grant as quoted in Nida, Toward a Science of Translating, 152.

- Nida, Toward a Science of Translating, 151.

- See third stage of translation process on the first section

- Divine here is intended as a reference to the Puritan ministers and theologians of the Westminster Assembly.

- Some of these characteristics were adapted from Morry Sofer, The Translator’s Handbook, 8th ed. (Jackson, MS: Schreiber Publishing, 2013); Nida, Toward a Science of Translating, 150-2.